CineVue: As Isaac Julien’s monumental 9-part double-screen film-installation TEN THOUSAND WAVES (2010) is approaching to the end of its exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art, Andrew Shiue, writer and founder of the New York City cultural site Beyond Chinatown, shares with us his review of this exhibit, which was originally inspired by the Morecambe Bay tragedy of 2004, in which more than 20 Chinese cockle pickers drowned on a flooded sandbank off the coast in northwest England.

REVIEW: ISAAC JULIEN’S TEN THOUSAND WAVES

by Andrew Shiue

Maggie Cheung as Mazu in TEN THOUSAND WAVES. All photos in this post are courtesy of Andrew Shiue.

Visitors to the Museum of Modern Art’s second floor atrium will most likely walk into Isaac Julien’s TEN THOUSAND WAVES video installation at some indeterminate point during its approximately 50-minute cycle. Cushioned benches and the carpeted floor encourage visitors to stay a while and watch. Many did one busy early Sunday afternoon and on a Wednesday afternoon, curious and trying to make sense of the nine double-sided screens suspended around the perimeter of the atrium.

Mr. Julien, whose other works have visited themes of migration and diaspora, was inspired by a 2004 tragedy (or “crime” as he has called it) in which twenty-three Chinese cockle pickers drowned in Morecambe Bay near Lancaster in northwest England as they were overcome by the incoming night tide. The victims were undocumented workers from Fujian Province who, like many others, went abroad for opportunity at the cost of being indebted to snakeheads and working for pittances. With this installation, Mr. Julien, per the press release, “explores the movement of people across countries and continents and meditates on unfinished journeys”. The title of the single screen version of this work, BETTER LIVE, explains the purpose behind these journeys.

TEN THOUSAND WAVES consists of three primary segments: a meta-recreation of the 1934 Chinese film THE GODDESS, scenes from the Southern Chinese countryside, and footage of the rescue operations at Morecambe Bay. They generally follow each other sequentially but also recur and overlap with each other. Interspersed are recurring scenes of pre-revolutionary, Mao-era, and present-day China.

The juxtaposition of the Mao-era and the present-day China.

The work opens with rescue footage and a title sequence of calligrapher Gong Fagen writing “浪”, the Chinese word for “wave”. Following this, the screens mix real footage and recreated scenes from early 20th century China. In this segment, fashionably dressed in a qipao, actress Zhao Tao, playing the titular prostitute in THE GODDESS who works to support herself and son, walks old Shanghai streets and rides the tram alone. The early 20th century backdrop is shown to be a production set. She continues in character in present-day China and goes to a hotel room in a high-rise building. Here, Maggie Cheung as Mazu, patron goddess of fishermen and seafarers, floats past the window.

Similarly, Mazu floats in the countryside, gliding over lakes settled between mountains in a picturesque countryside reminiscent of CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON. She is watchful and comes across peacefully napping fishermen taking a siesta.

The darkest segment relates directly to the Morecambe tragedy. This segment’s scenes fill the screens with dark, turbulent waters and actual aerial infrared video from the rescue operations. A gravely concerned Mazu intermittently appears on a few screens, searching helplessly. Accompanying the video is a plea to Mazu from Wang Ping’s poem The Great Summons:

Oh tender Mazu, Maiden of Silence

Hear the plea of your suppliant children

Our bones shatter upon the rocks

Our souls scatter across the ocean

Nothing is left of us

It’s not all helpless lamentations. Elsewhere, a selection from Small Boats, a poem also by Wang Ping that imagines the thoughts of the twenty-three who lost their lives, is defiant:

We know the [death] tolls…

We know the methods: walk, swim fly,

metal container, back of a lorry, ship’s hold

We know how they died: starved, raped,

dehydrated, drowned, suffocated, homesick,

heartsick, worked to death, working to death

We know we may end up in the same boat

Yet, they persevere for “a life like others [with] TVs, cars, a house bigger than our neighbors’”. As the poem is recited, drums pound in the background and screens showing modern China abruptly extinguish one by one.

Mazu links these disparate segments with her presence, transcending China’s past and present, fact, and fiction. In each, she wails “魂兮归来 / 魂兮歸來” (O soul, come home!). Zhao Tao’s Goddess and a fisherman are spooked by this beckon but do not know where it comes from. As a central element to the work, pre-existing knowledge of Mazu is helpful, but not necessary. The exhibition materials introduce her, and that she is supernatural being is clear to any viewer. However, the work confusingly portrays her as an observer rather than as the guardian she is supposed to be.

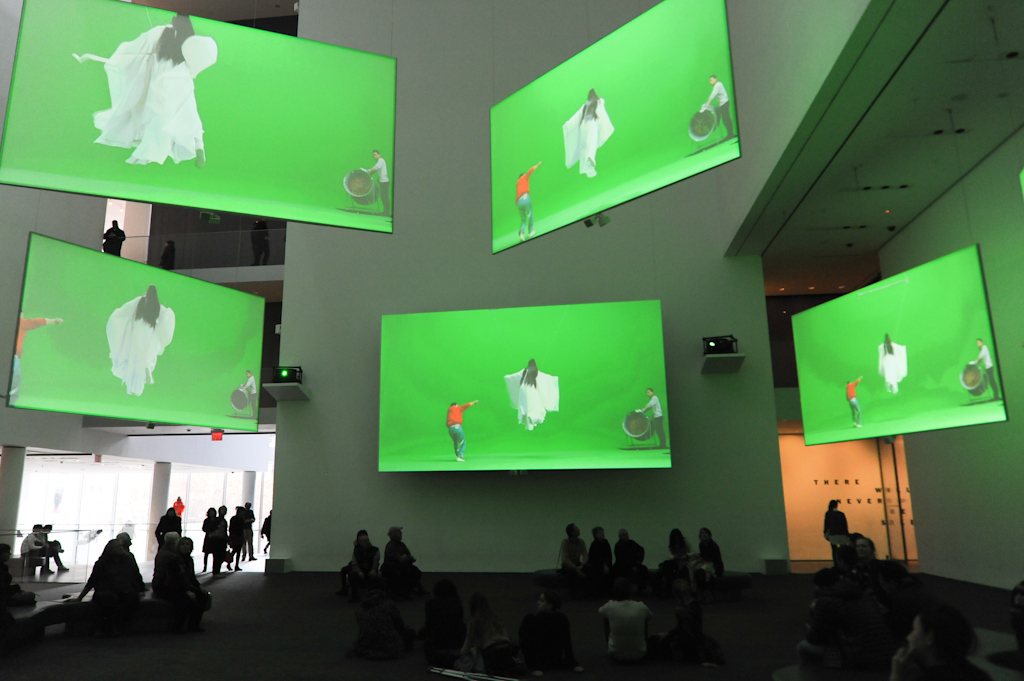

At one point, Mazu is revealed to be but an actress hoisted by wires in front a green screen. A closer look further exposes that the white-robed actress playing Mazu wasn’t even Maggie Cheung. The Chinese diaspora in Asia who reached their new lands may give thanks to her for a safe journey, but the deity of TEN THOUSAND WAVES is a fiction.

Revelation of the shooting process in front of the green screen.

TEN THOUSAND WAVES’ mode of presentation, projections on both sides of nine screens measuring up to 23 feet in width, is unique and massive. This installation at MoMA is the first to stagger the screens at different heights, 20 or more feet off ground level (apparently, the engineering behind the installation was quite an accomplishment). Rather than navigating through the ground level screens that bring viewers closer to the images but allow them to see fewer screens at one time, viewers at MoMA can yaw between many screens.

In an interview with The Guardian, Mr. Julien said, “I’m trying deliberately to frustrate the ontological gaze of the spectator. In the gallery, you won’t be able to see the whole work at once, so any narrative you establish is necessarily fragmented.”

Often, all screens are active, but during the length of the work, any number of screens may be dark. Sometimes, the screens juxtapose different scenes from different segments. As described above, there is a moment when most screens show images of violent waves, but one or two show images of Mazu. Other times, the screens show the same scene but from different angles or slightly different temporal positions. The viewer quickly realizes this.

This fractured viewing does not make a better narrative. When the screens show similar images, nothing is gained or lost if the viewer covers many screens or misses any. The viewer does not see the exact same images across different screens, but they are not really different. They are not perspectives with new information.

However, when the screens show different images, the situation becomes “look now or you’ll miss it”. For example, in one scene, many screens show Zhao Tao’s goddess walking the streets at night. One screen shows for a few seconds her attempts to solicit a customer. If you don’t see this, you may not realize that she is a prostitute (the exhibition materials mentions THE GODDESS but does not explain the film or the character). Beware of being lulled into thinking the screens are showing the same thing and focusing on a few in a particular direction.

Mr. Julien’s statement in The Guardian suggests there are different narratives, but the screens tell a single narrative which can be incomplete if you miss crucial images.

The myriad of videos are intriguing. Cinematographer Zhao Xiaoshi’s shots are cinematic. Zhao Tao is poised and glamorous. The recreation of THE GODDESS invokes glamour and mystery, and images of looping elevated highways and the Oriental Light sculpture show present-day Shanghai to be a marvel. Maggie Cheung flying through the misty countryside is like a fairy tale. The glitchy, interlaced rescue video is raw and tense.

The audio aspect of the work is engaging. Music by Jah Wobble and the Chinese Dub Orchestra and Maria de Alvear sets shifting moods to complement the video. When we see faux Mazu’s robes being blown by a large fan, it sounds like the helicopter from the rescue footage. The acoustics of the cavernous atrium magnify the soundtrack to a grand scale. However, the large space also makes many of the spoken words difficult to understand.

Wang Ping’s dirges are essential to understanding the theme of seeking a better life. Unfortunately, their recitations appear unexpectedly. Those not invested to staying at least fifteen minutes might miss them completely. Without them, TEN THOUSAND WAVES is a collection of videos that leave the viewer wondering what it is they are watching.

With the length of the work and its vague narrative, Mr. Julien has not made an accessible or easily comprehended work. The viewer is frequently left wondering the purpose of different scenes. Why is there a scene where Zhao Tao sits across from artist Yang Fudong? Why does Mazu visit the sleeping fishermen? Why are we looking at busy Shanghai streets? Parts of the work clearly relate to Mr. Julien’s stated themes, but there are too many disparate images to absorb and synthesize. As a whole, the work is unfocused and the idea of transplanting one’s existence for a better life is lost.

Zhao Tao as the Goddess sitting across from Yang Fudong.

Furthermore, the impact of tragedy at Morecambe Bay is lost amongst all the pretensions of the presentation and the narrative. Towards the end, we see photos of some of the victims and their personal effects. One or two screens show a drowned body, while others show a mournful Mazu. You might miss either, depending on which direction you’re looking. The brevity of this segment and the obfuscated presentation of the themes are a disservice to the twenty-three who lost their lives and others who have ended up in the same boat.

Nevertheless, TEN THOUSAND WAVES is worth seeing if only for its elaborate mode of presentation. It is a work that requires patience and benefits from more than one viewing. Being familiar with the images and their sequence the second time I visited the installation, I allowed my view to roam much more and was better to synthesize the images and narrative. The two calligraphy scenes mark the beginning and the end. It is unlikely that you will show up at the beginning, but stay for one whole cycle. Be sure to constantly shift your view so that you can absorb as many screens as possible.

An abridged, single-screen version of TEN THOUSAND WAVES as well as a Q & A with Isaac Julien can be seen here. Wang Ping’s poems The Great Summons and Small Boats can be read here. MoMA’s behind the scenes look is also interesting. TEN THOUSAND WAVES is on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York through February 17, 2014.

PostScript: Five people were convicted of human trafficking or money laundering charges stemming from this incident. February 5, 2014 marked its 10th anniversary. The victims have not been forgotten. Last year, a sculpture named Praying Shell was dedicated at the site where the lives were lost. The British press has also revisited the tragedy and honored the victims not just by retelling the tragedy but looking at current conditions of others seeking better lives.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Andrew Shiue is the founder of Beyond Chinatown, a site dedicated to Chinese topics and events in NYC that are outside of mainstream discussion and push arts and culture forward.