By Alexa Strabuk

Centipede still from TYRUS. Credit: Sara Jane Boyers

It was a muggy summer day in New York City and typically unbearable. Escaping my air condition-less apartment in Brooklyn, I found myself at the Met, seeking refuge there until the evening brought livable temperatures and I could go outside again. Walking through room after room of eulogized Great White Men, I grew a bit weary. I’m no art critic, but I am a transnational woman of color, and after making my way through several exhibits, the art began to lack in originality. Turns out Europe and America have an alarming tendency for documenting war and gilded aristocrats with very little variation. I suppose that much monotony really is some kind of small accomplishment. It’s almost impressive.

Sure, there are entire wings of the museum dedicated to non-Western art, but the American Wing was of particular interest that day. I walked into a room where Thomas Hart Benton’s striking “America Today” mural, a four-wall panorama of 1920s America in all of its industrial glory, was installed for viewing. It was the kind of impressive art that unfailingly stirs up a displaced patriotism within me, inciting a deeply buried nostalgia for a time that excluded people who looked like me from its narrative. I’d become an objective onlooker in my own reality. To be clear, I’m talking about not seeing anybody Asian, don’t even get me started on how difficult it was to find Asian female representation.

There has always been some debate over whether the fine arts are exclusive, elitist, and well…white. Some argue that participation in the arts, both appreciation and production, is strongly related to socioeconomic status. Others claim that some public education programs actually do provide low-income people of color the chance to engage with the arts and that the once-rigid standards of the classical have since fractured. I believe both to be true. While the art world has diversified somewhat, traditional museums still tend to feature European or Euro-influenced art pretty heavily. Artists like Whistler and Van Gogh even looked at Asian prints for inspiration. In essence, our influence was there and we were not. Sound familiar, pop culture?

Thomas Hart Benton’s mural “America Today” installed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Credit: Anna-Marie Kellen, The Photograph Studio/The Metropolitan Museum of Art

As I continued through the exhibit, I wondered how American textbooks, media, and even fine art had excluded me, and the people that looked like me, from history so easily. Poof. Like we never existed. And of course, the rational part of me knew that Asians had lived in America during and prior to the 20th century, yet somehow there was very little evidence to substantiate my logic. Our stories [we][a]re either found in the margins or nowhere at all. Just as I was about to move on from the American Wing, I spotted “Self-Portrait as a Photographer” by Japanese American artist Yasuo Kuniyoshi. Two things struck me: Kuniyoshi’s reflexive exaggeration of his own Asian facial features and the painting’s vague familiarity.

I’d seen it before. The painting was part of a significant rise in “Orientalist” expression during the 1930s, an art movement that included Tyrus Wong, whose story was chronicled in Pamela Tom’s documentary TYRUS (2015). I’d remembered the piece because of its influence in establishing cultural ownership for Asian American artists during a time when Chinese immigration was barred, and when Asians could not marry outside of their race, testify in court, or own property. Frustrated by what little representation I saw at the Met that day, I realized the documentary’s renewed significance in my own life. The first time I saw TYRUS, I left inspired. During my second viewing, I left compelled.

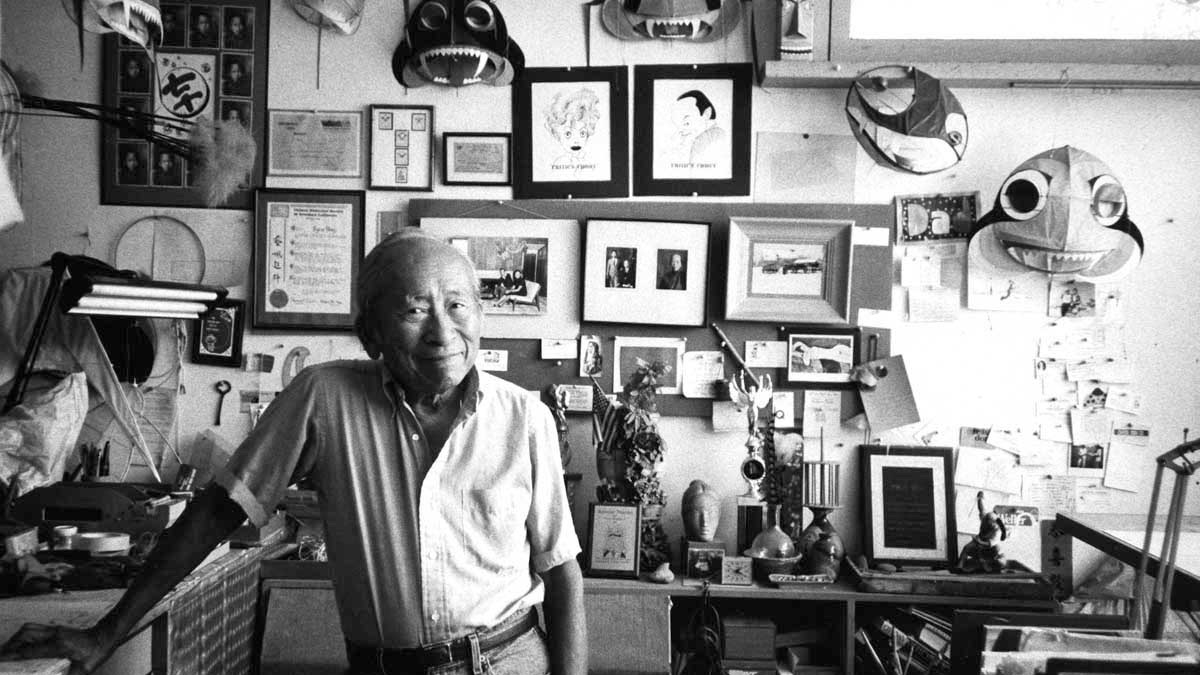

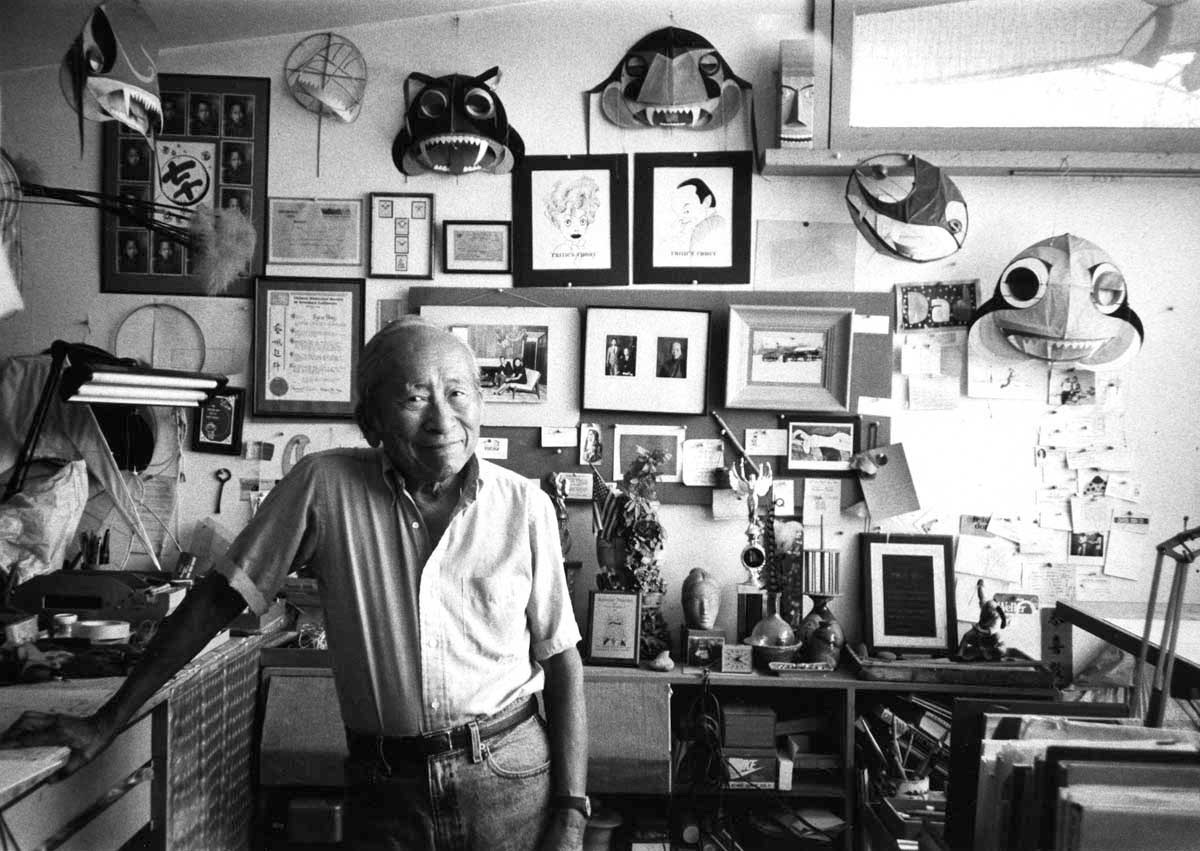

Tyrus Wong in Kite Studio. Credit: Irene Poon Anderson

Born in Guangdong, China in 1910, nine-year-old Tyrus Wong journeyed to the States. He never saw his mother again. After being interrogated at Angel Island for several “miserable” months, he was released and joined by his father. “I liked to draw and paint. Those are the only things I liked to do,” Wong says in the film.

As a young boy, he studied calligraphy, often without ink, leaving impressions in newspaper to get his practice in. Though his father considered art an unprofitable, erratic career, he supported him and even borrowed money to help pay for his son’s studies at the Otis Art Institute. It was a sacrifice that Wong would never forget.

An expository work, TYRUS combines traditional archival footage and interviews with experts, historians, and with Wong himself. Director Tom zeroes in on the immigrant experience in a way that the American Wing of the Met couldn’t quite capture: as a complicated balance of old and new. The film reminded me that my identity is more than a small box that I check off while filling out forms. My immigration is a protracted struggle; it didn’t stop when I crossed the border. It sticks with me every day. What amazes me most about Wong is that he created an aesthetic that was distinctly his, focusing on shape rather than detail, and employing both Eastern tradition and Western technique. That’s what made his work unapologetically Asian American.

Wong, along with Hideo Date, Benji Okubo, and Gilbert Leong helped establish Asian American art as a genre, participating in the country’s first ever “Oriental Art Exhibition.” Their work would go on to catalyze a broader public interest in East Asian expressionism. Unfortunately, all momentum came to a halt when the Great Depression hit. Painting watercolor art and contracting commercial work, Wong did whatever he could to survive, but it was not enough. He was eventually hired as a concept artist at Disney, an “all boys club” where minorities were numbered, women were non-existent, and the bigoted sentiments of the time ran rampant. It was here that he worked on the prolific Disney classic Bambi (1942).

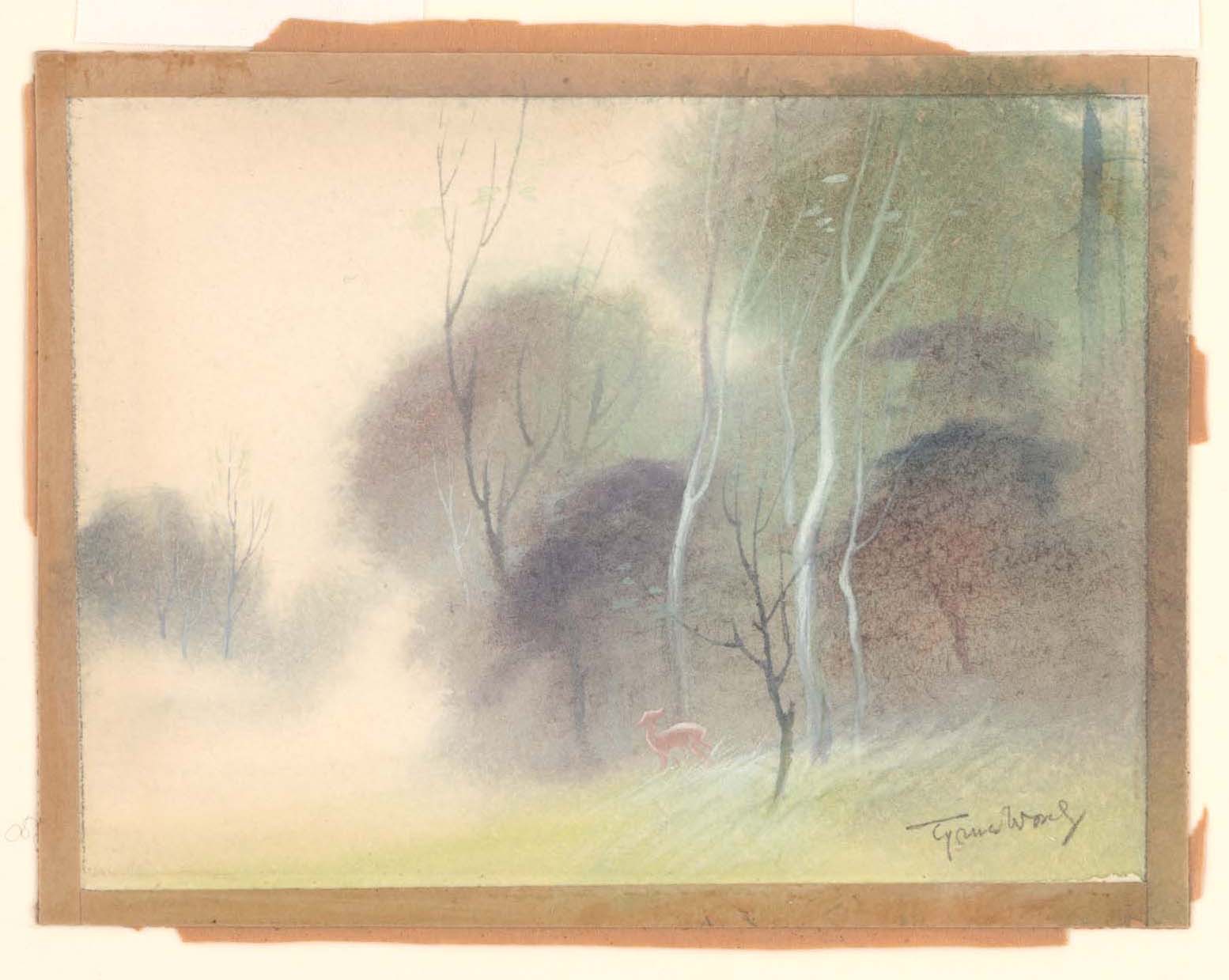

Tyrus Wong’s Bambi. Credit: Collection of Tyrus Wong

Back then, the entire studio cleaved to one artist and Wong’s sketches became the primary inspiration for the film’s art. Let me just say: I love Bambi. Despite how racialized the animals of children’s films can be, animals were always characters I could identify with… at least more than I could with white humans. Out of curiosity, I re-watched the classic to look out for Wong’s influence. His style is impossible to miss. You can see it; the use of light and the soft background in contrast to focused, sharp characters. That’s all him. But, in typical corporate fashion, Disney capitalized on Wong’s talent with little-to-no regard for much else and he was credited as a background painter. He was later let go.

Wong went on to become a motion picture illustrator, painting Christmas cards on the side for Hallmark, and raising children with his wife. On paper he looks like what the American Dream is all about–and it’s true that Wong was lucky in some ways. Although extremely overdue, people now recognize his contributions and respect him for his work. By contrast, many Asian immigrants continue to live below the poverty line, working minimum wage jobs, struggling with language barriers, and suffering from exploitation based on citizenship status. Still, Wong’s success in his own country didn’t come without the price of lifelong racial discrimination and the erasure of his accomplishments. I’d never heard of him and there’s something to be said for that.

Tyrus Wong was someone who loved his country and his roots, proving that those two things don’t need to be mutually exclusive. Moreover, he demonstrated that Asians have just as much of a claim to America as anyone else, even in the oh-so-exclusive fine art world. One of Wong’s daughters says that her father is most proud of his success as an Asian American. That, I assure you, is no small feat. It’s hard to be what you don’t see. I cast myself as the sidekick for years, the go-to fly on the wall, because I didn’t know I was capable of being much else. It’s about so much more than just representation. It’s about reformation. I didn’t study Grace Lee Boggs, Yuri Kochiyama, or Larry Itliong until I was in college. A few weeks ago, I learned about Tyrus Wong.

Quick update: I’m not a sidekick anymore. And I’m in the very best of company.

Alexa Strabuk is in her fourth year at Pitzer College, pursuing a bachelor’s degree in media studies and digital art. She is a writer, filmmaker, and activist. In 2015, the Asian American Journalists Association recognized her for her work as an up-and-coming reporter.