By Alina Shen

Photo by Marion Aguas (marionaguas.com)

True to its name, An Asian American Film Thing was a run of short films and trailers, followed by performers. The lineup featured films from the emcees, Hye Yun Park and Angel Yau, as well as directors SJ Son, Woody Fu, Theresa Loong, Joon Chung, Tanmaya Shekhar, Anna Mikami, Esther Chen, and David Fung. Jen Kwok performed keyboard and vocals, Jessica Rowboat performed guitar and vocals, and Wo Chan performed lip-sync in drag. From nail salons to war documentaries and family histories to Asian Americans interviewed at random for a YouTube cut, the night covered a full range of film setting, purpose, and style.

Right as the show began, filmmakers were called up to the stage to give a quick intro about their piece. Onstage, they became a half circle of inside jokes with the audience who they made comedian quips about, alongside sincere if brief descriptions of their work. One film was described as a satire of a Korean American woman opening a “nail salon, of all things.” Another was about intragroup racism among Asians. “You’ll get it if you have Asian immigrant parents,” said Woody Fu. He added that he would “like to get [the audience’s] emails to get more Asians at my show,” just so there would be more folks in his usual audience who would get his jokes. The audience that night laughed.

Were we being reminded here that Asian American films, a token of diversity to white audiences if on their radar at all, are a series of inside jokes and doublespeak when reflected back at Asian American audiences?

The first film, SOOJUNG DREAMS OF FIJI, seems to answer that. It is a beautifully produced and tightly paced satire in the genre of JIRO DREAMS OF SUSHI, a documentary following a Japanese sushi chef dreaming of reaching perfection in his craft. Soojung is a Korean American woman pursuing her craft by opening a highly successful nail salon. She dreams of Fiji pink, an Essie brand shade of nail polish and the only one her high end mani-pedis come in. We watch as white women keep getting Soojung’s name wrong, but are duped into paying $600.99 per manicure (the final 99 cents tacked on as an ironic homage to bargain pricing). In one scene, a white woman customer bows to Soojung as a greeting, who bows back. Each time the customer rises, she notices that Soojung has not yet, and bows again. They ceaselessly exchange bows for the rest of the cut.

Still from SOOJUNG DREAMS OF FIJI

Ultimately, the tension and depth of the documentary emerges from the strained relationship between Soojung and her mother. When Soojung opened her nail salon nine years ago, her mother disowned her. The actors’ exaggerated portrayal of the disapproving Asian parent and the stoic and hardworking Asian American daughter come off as comical, but not demeaning. As audience members, we are not here to poke fun at them or laugh at their expense. Instead, we are invited to laugh at those who genuinely believe in these tropes, those who look something like the forever bowing, name-mispronouncing, pay-extra-for-the-authenticity, wealthy white women. By accepting and acting on these stereotypes as truth, the white women become caricatures themselves.

In contrast, Soojung and her mother are humanized by their relationship with one another. Her mother is both a tongue-in-cheek portrayal of the disappointed Asian parent trope and a glimpse of something heartbreaking at the core of this film: what we do for and because of our family is something we must never tell them. To tell them is to diminish, somehow, our unconditional love and drive. In the final voiceover, we learn that the nail salon is built around Soojung’s only memories of when she and her mother spent time together. On Sundays, sitting in the bathroom that her trophy husband father had just cleaned, her mother would paint her nails a “soft, brilliant” shade of pink, called Fiji.

SOOJUNG DREAMS OF FIJI is a film that encapsulates the range of tools that comedy and humor can have within an Asian American cultural space. Depending on who is watching, multiple meanings can be made out of the same scene. What might read as a one-dimensional comedy to a white audience actually contains themes of caricature, family tension, and light ribbing of this very audience. Through this multifaceted lens, we can have empowering private scripts in which we, with Asian American experiences, are the only ones who can read them. In context of a history of cultural production that has used our joy, embarrassment, and pain to trap us into immutable tropes, the film is a brief flash of what Asian American cultural production could be.

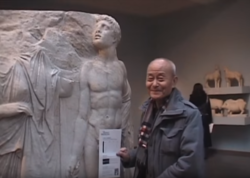

Closing the film lineup was a clip of a film directed by Theresa Loong called EVERY DAY IS A HOLIDAY. The film explores the untold family history of her father, drafted in Malaya (now Malaysia) to be a soldier for Britain during World War II. He becomes a prisoner of war to Japan. Nested in the genre of Asian American family stories and their relationship to a global history, the film alternated between black and white reels of the battlefield and home video clips of Theresa Loong’s father, now older. In one shot, the director visits a museum gallery of naked sculptures with her family. Her father poses with one, then covers up the sculpted genitals with a brochure, grinning. The two reels are juxtaposed, as if to ask the audience: How can a young soldier and prisoner of war become this father? How can this figment of global history also be my dad?

Still from EVERY DAY IS A HOLIDAY

More than any other film, Loong’s film strikes closest to the heart. To expose family and family history to the world is not an easy choice. Seeing her father in the museum, I saw my relationship with my own father. Loong’s father’s slapstick humor and his gruff demeanor were all too familiar to me. When Loong asks her father about the brutality of his uncle and adoptive family’s habit of kicking him every morning to wake him up, he dismisses it as just part of needing to be awake. Loong asks him about becoming a prisoner of war. “Did you feel scared?” she asks. No, he was only nineteen. Too young to be scared, he responds. It is an absurd answer because we are scared at every age, but after watching him deliver that line, I can believe his way of telling the truth.

In this film and for my father, humor is a form of agency when confronting past violence. The familiar brand of dad goofiness is a defense mechanism and a way to gloss over the memories. We find that humor not only humanizes us, but also gives us power. The inside joke doesn’t just reinforce our ability to cope with a chaotic life, but also reframes the past. As a jokester, we are not downtrodden, we are just biding our time.

Theresa Loong’s father holding a framed portrait of a soldier with text that says, “This man is your FRIEND… Chinese”

Some pieces in the lineup did not match the depth of these two films. These other films seemed to focus on proving to the latter that Asian Americans could be like you, mainstream, white audience, while avoiding explorations of assimilation that question its purpose. For example, the abbreviated rendition of WHAT IF SPIDERMAN WERE ASIAN? centered an Asian American Spiderman’s wounded pride when Mary Jane appeared disappointed over her unmasked hero’s appearance. We laugh because of the reveal, but there is an unaddressed tension. Peter Park’s conflict and desire is to be accepted as Spiderman, the white masculine hero. Yet he does not appear to question or reference the historic systems put into place that produce this desire at all.

The documentary DO ASIANS CARE ABOUT POLITICS?! (Fung Bros.) felt particularly limiting in the literal questions being asked. The first question: Why are Asians left out of national debates? The sampling of responses: “Communities are not that strong.” “It’s our fault.” “We’re just very comfortable where we’re at.” All responses indicate a sense of group complacency, and a general consensus that Asian Americans are all socially and economically well-off or at least at a middle-class status. The video is shot near New York University, one of the most expensive private universities in the country, and in lower Manhattan, one of the most expensive places to live in the country. As the only voice being represented in this sample demographic, these responses can send a dangerous message.

One interviewee said, “Asians tend not to speak up, so it’s partly our fault.” Despite the colonialist constructed imagining of the Chinese as hardworking and docile, Chinese American railroad workers went on strike in 1867 for a higher wage and safe working conditions, but were starved out and forced back to work. When Filipino farmworkers in California went on the Delano Grape Strike in the 1960s, refusing to pick grapes, they prompted a national boycott. In 1968, the Asian American students joined in solidarity with black, Chicano/a, and indigenous students to form the Third World Liberation Front at San Francisco State University. They protested the curriculum at their university, pushing for ethnic studies and a history that reflects their lives. Undocumented Asian Americans have historically and presently wage campaigns to push immigration policy forward. When the interviewee implies that Asian Americans are quiet and exclusion from national politics is our fault, and when the Fung Bros. air it without questioning or contextualizing the answer, the video denies the long histories of Asian Americans organizing for change and the present movements of students fighting to learn about them.

Still from DO ASIANS CARE ABOUT POLITICS?!

Unlike EVERY DAY IS A HOLIDAY, which asks the Asian American audience to examine the untold stories of our people, DO ASIANS CARE ABOUT POLITICS?! becomes a much different question when placed alongside Loong’s film. How would the father respond? How might the reasons he gives be different from those interviewed?

From watching this video alone, the Fung Bros’ production style is one that points out an issue, shrugs, and claims to start the conversation without finding it necessary to dig any deeper or do more than reinforce the idea that the problem exists. By the end of the video, we heard a chorus of Asian American interviewees establish that the lack of Asian American representation in national politics can be addressed with a louder and more assertive “voice,” and giving a vague call to “get involved, any way you can.” While this is a fairly straight-faced film, the Fung Bros. then invite the audience to find humor at the idea of a “ratchet” Asian American. The interviewer offers the first of the closing questions: “Do you think Asian Americans should get more ratchet?” (Ratchet: Hip hop slang for a bad-mannered woman, and Louisianan regiolect for “wretched.”) The answers were a definitive no, a surprised no, a confused no, and then a laughing yes.

From the rather arbitrary choice of wording, the Fung Bros. seem to have been asking, should Asians appropriate blackness to speak up? We are asked to laugh at the ridiculous image of an Asian American stirring up trouble, of acting with a certain uncharacteristic recklessness associated with blackness in the United States. In asking us to laugh at this, the Fung Bros. rely on the stereotype, confirmed by the selected interviews, that Asian Americans are reserved and docile. By the end of the video, it is unclear whether the title question, posed with urgent punctuation, is ever answered or approached, and the audience is left without a sense of what the purpose of asking could be.

It is easy to be a critic and pick holes at what was missing at an event that was, in fact, hilarious, creative, and full of young Asian American actors and filmmakers trying to network on a Saturday night. But to be a critic is to hold out higher standards for Asian American cultural production. There was a strikingly few number of films that engage with or respond to social issues beyond representation in the media for Asian Americans. And then the question becomes, representation to what end?

What other questions do we have for Asian Americans besides representation (in the media, in politics, in cultural spaces)? And what can we expect of Asian American film and performance? Perhaps we look for representation in the media and in politics to feel seen and heard. However, without context, representation is only surface level. When we engage deeper with representation, we learn that we have always been there, throughout the history of the United States, as cultural producers, and as powerful communities with many faces. We have shared histories as the entrapped and revolting worker, and layered relationships to socioeconomic status which has been tied to skin color and access to wealth. We have fluid experiences with sexuality and gender, and are shaped by our proximity to whiteness and relationship to blackness.

After attending An Asian American Film Thing, I want to believe that there is film and performance for a critical Asian American audience. The tension between an Asian American filmmaker and a filmmaker who is Asian American could be a matter of semantics and audience opinion. Yet if the inside jokes embedded in Asian American film and performance speak back to us and pull the specific audience to see in multiple meanings on screen and off, then we can find art for our time that can do both.

After all, filmmakers are cartographers, shaping space and time for audiences so that we can exist briefly between reality and an imaginary place. Ultimately, the most iconic moment of the night is Wo Chan shimmying onstage in a glittery gold bodysuit and gown, catching and throwing all the soft light in the room while simultaneously performing to a lounge singer’s ballad and admitting his confusion over the reputation of bottoms, imagining something different for all of us.