Written By: Nathan Liu

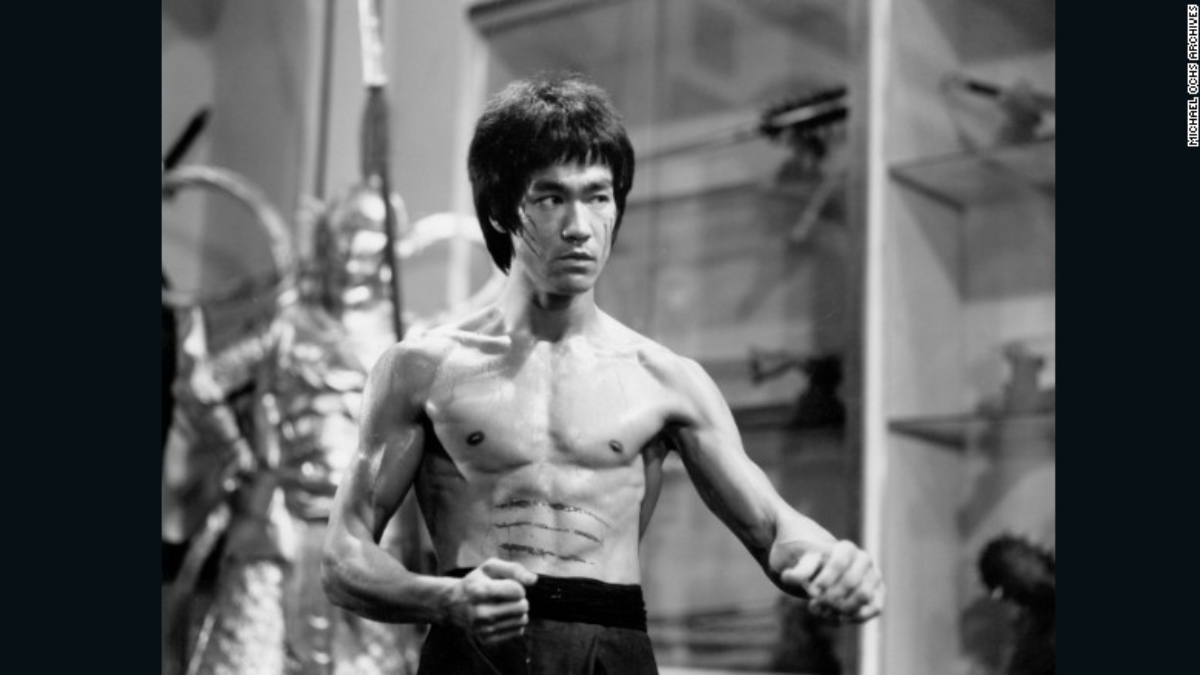

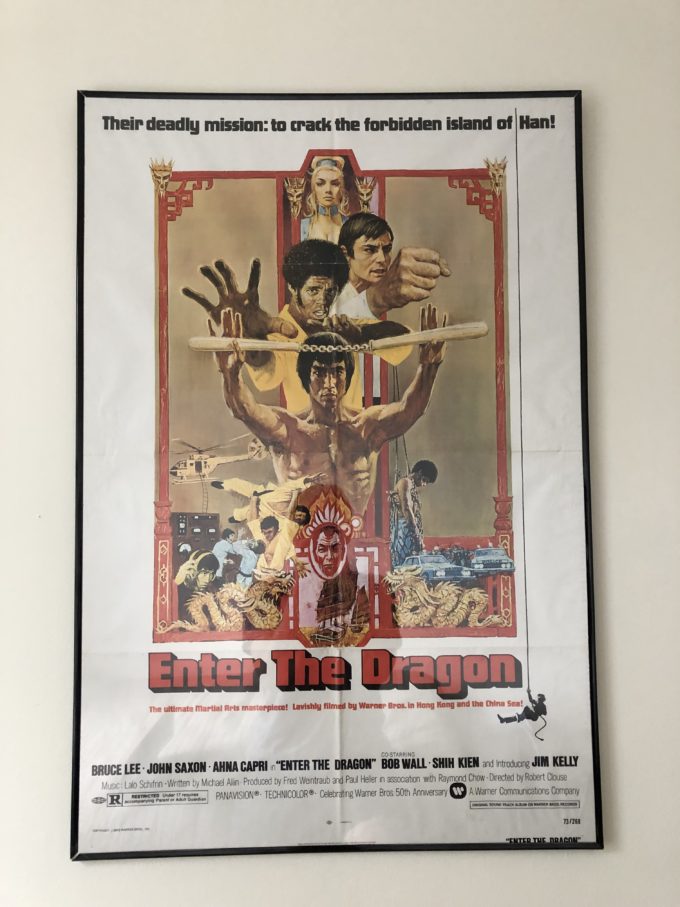

Bruce Lee. What more do I need to say? You all know him, the actor and martial artist whose hit films helped bridge the gap between East and West. He’s the man who created Jeet Kune Do, the hybrid fighting style that paved the way for modern MMA. He’s the guy whose films were so influential that not only did one of them, “Enter The Dragon,” get inducted into the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry, but they also inspired an entire genre of movies called “Bruceploitation,” where Lee look-alikes would try to capitalize on his success. He’s a person who has had documentaries (2000’s “Bruce Lee: A Warrior’s Journey”), biopics (1993’s “Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story”) and miniseries (2008’s “The Legend of Bruce Lee”) made about him. Statues of the man can be found in Hong Kong, Bosnia, and Los Angeles. To put it simply, he was, and still is, a big deal.

Every aspect of his life — from his birth in San Francisco, to his childhood in Hong Kong, to his tutelage under Ip Man, to his college years in Seattle, to his struggles in Hollywood and his subsequent return to Asia — have been meticulously detailed. His tragic death at the age of 32 alone has become the subject of urban legends, with some people claiming that his family was cursed. At this point, Bruce Lee has ceased to be a flesh and blood human, and has instead become a folk hero, as ubiquitous and larger-than-life as John Henry, or the Monkey King. That may honestly be the best way to analyze him: as a piece of folklore.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, folklore is “the traditions and stories of a country or community.” However, Merriam-Webster defines folklore as “traditional customs, tales, sayings, dances, or art forms preserved among a people.” And according to the American Folklore Society, it is “the traditional art, literature, knowledge, and practice that is disseminated through oral communication and behavioral example.” None of these are exactly the same, though they all contain the common element of people of a particular community telling each other stories about a certain thing over many years. And why do they do this? Again, the definitions vary, but one common element seems to be the idea of unity. By telling stories over and over again, and passing them down through generations, a group can reinforce its own identity.

Bruce Lee’s story has definitely been shared throughout the world, particularly among the Chinese, and his success certainly has created a sense of pride among Asian and Asian American peoples. Jeff Adachi’s 2006 documentary “The Slanted Screen” deconstructs the various images of Asian men that have been created in Western media, and features a fairly long section dedicated to the impact that Bruce Lee had on young Asian males. Several of the interviewees talk about how Bruce inspired them. One, actor Will Yun Lee, describes Bruce as “… the epitome of cool. He was James Dean. He was Michael Jordan. I just felt proud to be Asian because I saw somebody up there on the screen doing what he did.” And director Phillip Rhee explains how Bruce’s success “… gave a lot of Asian males pride. “We were able to walk down the street with our heads up.” So Bruce’s story is one that’s been passed down through several generations, and has created a sense of pride and unity within a particular community. That comfortably seats him in the realm of folklore.

But folk tales, as we all probably know, can be reinterpreted. They can be retold. The lessons that they seek to impart can be questioned. Why do you think there are so many revisionist fairy tale movies, like 2020’s “Gretel & Hansel,” 2012’s “Snow White and the Huntsman,” and 1996’s “Freeway” (an adaptation of “Little Red Riding Hood”)? People like to question the morals and wisdom of those original tales. And Bruce’s legend has certainly been questioned.

Several of the interviewees in “The Slanted Screen,” such as playwright Frank Chin and comedian Bobby Lee, argue that, in his own way, Bruce reinforced stereotypes. As Bobby Lee puts it, “Bruce Lee definitely made it harder for Asian men, in terms of the bar, what people saw you as. Like, I had people come up to me and ask, ‘Do you do Karate?’ No. But it’s because of Bruce, people think that I know karate.” And he’s not wrong. The stereotype that all Asian people know martial arts is one that persists to this day, largely thanks to the media that gets produced. Even now, nearly five decades after Bruce’s death, a large portion of the Asian-centric content made in Hollywood focuses around martial arts. In 2019, there was the AMC series “Into The Badlands,” the Cinemax show “Warrior” (based off of an original idea from Bruce) and Netflix’s “Wu Assassins.” This year, we have the live-action “Mulan” coming out, and next year, we have Marvel’s first Asian-centric superhero movie, “Shang-Chi And The Legend Of The Ten Rings.” All of these feature Asian characters doing Kung Fu. Now, by itself, that isn’t a bad thing, since martial arts is a part of many Asian cultures. It is not, however, these societies’ sole, defining trait — a fact that might be lost on non-Asian audiences who see it, and only it, featured in movies. So in this way, by popularizing the martial arts genre, it could be argued that Bruce broke some stereotypes, while simultaneously creating others.

Does this mean that Bruce should be forgotten, or written off as someone who simply reinforced regressive images? Of course not. But I do think it would be better for the community as a whole to focus less attention on him. Even now, new Bruce Lee content, like the aforementioned “Warrior,” and his less-than-flattering cameo in Quentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon A Time in Hollywood” is getting produced, and I don’t know if that’s what modern Asian American audiences need. The issues that Asian actors like Bruce were facing back in the ‘60s and ‘70s aren’t the same ones being dealt with now. And by focusing so much on the achievements and experiences of one man, it overlooks the fact that countless other Asian American artists and activists were, and still are, working to create a more inclusive world. Bruce changed the game. There’s no denying that. But his story has been told many times, in books, documentaries, movies, and miniseries. It doesn’t need to be told again. There are new stories that can, and should, be passed on in the same way his story was. We should tell stories of Asian women, members of the LGBT community, and people with disabilities. All are folk heroes in their own right, and all deserve to have their legends be known.