A conversation between Celine Song and Jeff Yang

On January 23rd, the Lila Acheson Wallace Auditorium at the Asia Society was packed with people who had come to hear a conversation between author Jeff Yang and director Celine Song. Just that morning, Song’s directorial debut feature, “Past Lives,” had been nominated for Best Picture, and Best Original Screenplay Academy Awards.

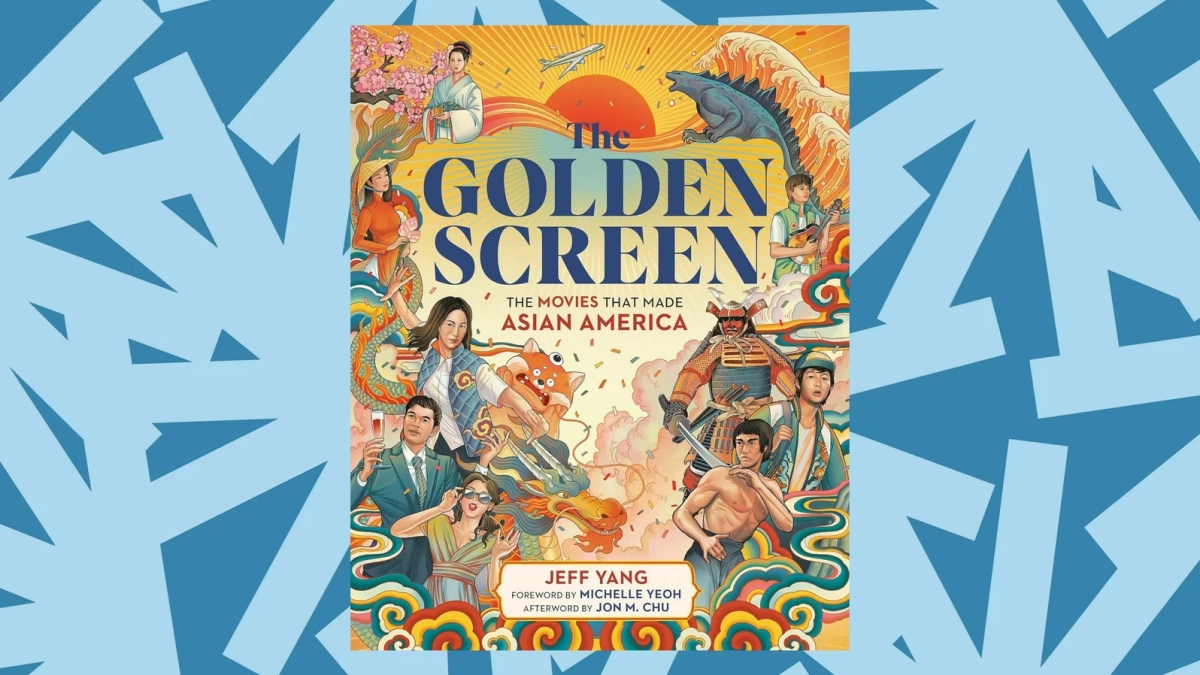

Yang, the moderator for the night, recently published his book, “The Golden Screen,” a deep dive into the history of Asian American representation throughout Hollywood. His insightful and thought-provoking questions led Song to reply with seemingly off-the-cuff answers that left the audience in tears.

Before the conversation, I had the chance to speak to an attendee, Alyse H. She said she was there for “authenticity.” She didn’t want anything “sugarcoated for the white people.” Instead, she wanted to experience a conversation for the Asian American community.

In his intro, Yang noted that the emergence of Asian and Asian American cinema into the spotlight did not just happen overnight. In fact, “this emergence took the entire history of Hollywood for us to earn.” He went on to explain that historically, Asians have been represented in films in a “twisted or toxic, or a tasteless fashion … representations that were internalized by Asians to normalize not taking up space, to defer to louder voices, and to discount our achievements.”

Overcoming this obstacle was something that Song noted in her desire to write “Past Lives,” a film that was heavily inspired by her real-life relationships and experiences. She noted, “if it is true to the way it feels to me personally, I know that there’s going to be more than one person who’s going to feel similarly.” It became about depicting what it “actually feels like to live right now … That is something I just know that anybody that has more than one culture can feel connected to.”

This feeling and belief that an audience will connect to a story despite not sharing the culture or ethnicity, is one that many Asian American creators have been robbed of over the years. They were consistently told that their stories were too niche or fringe, and that they were unrelatable. But Song pushed against that and held firm in her belief that this story is relatable to all. She explained, “We’ve all had to live through vast amounts of time and space … in a way, we’re all immigrants of ourselves from our past to our present.”

However, Song didn’t always feel that her story was accepted by all. She knew that “Past Lives” was a bilingual and bicultural story. However, the industry was quick to tell her that this would be a challenge. When she first began writing the script, Song tried to use Final Draft, a screenwriting software that is industry standard. She learned that at the time, Final Draft only supported the English alphabet, which made writing dialogue in Korean nearly impossible. It felt like a “silent way to say that [Hollywood is] not interested in a bilingual story … it was discouraging” she said. “ Eventually, she found a program that supported both the English and Korean alphabet and was able to create the Oscar-nominated screenplay we all fell in love with.

In this conversation about diversity and representation, Yang noted that both “Past Lives” and “Everything Everywhere All At Once,” the 2023 Academy Award Best Motion Picture of the Year, were both distributed by A24, which meant that “Past Lives” was “coming into the space” of another critically acclaimed Asian American immigration story. However, “Everything Everywhere All At Once” is almost the polar opposite of “Past Lives”. It’s all about maximalism; showing every possibility of every choice a person could make. Whereas “Past Lives” shies away from the “diaspora multiverse” and is a micro view of the Asian American immigrant experience. Yang described it as instead of a multiverse, “Past Lives” gives us the “luxury” of experiencing “verse after verse” of this one, specific story..

When Yang asked if the vast differences in the two films made it difficult for “Past Lives” to come into the world, Song answered, “‘Everything Everywhere All At Once,’ which is a completely different film than ‘Past Lives,’ they can all exist and be celebrated in the same way and in different ways.” That “diversity within diversity” is what excites her. The fact that not all Asian American stories could or should fit one specific mold, that just like the people, the stories and methods of storytelling are infinite.

After the conversation, I spoke to Justine, an aspiring filmmaker who said that the conversation helped her see storytelling and screenwriting in a new way. They were moved by the humanity of it all. How it was just a story about humans. And isn’t that what we’re all looking for? An accurate representation of ourselves and our stories on the big screen? Yang put it perfectly in his introduction when he said, “the truth of a movie emerges in the experiential intersection between our memories, our identities, and those flickering, mesmerizing, 40-foot tall images on screen.” The “mirror of the silver screen” is shifting to represent and depict authentic Asian American stories, and it’s about time.