Written By: Nathan Liu

Since I started writing for CineVue, I’ve done my best to spotlight early pioneers in the film industry. People like Sessue Hayakawa, Hollywood’s first Asian leading man, and Miyoshi Umeki, the first Asian actress to win an Oscar. And while I’m eager to do so, I find myself grappling with an uncomfortable question whenever I decide to spotlight one of these forgotten figures: what’s the point? Why should we, as Asian Americans and film fans, study these people? Miyoshi Umeki only made five movies in Hollywood before retiring. Likewise, most of Sessue Hayakawa’s work from the Silent Era has been lost. That’s why I decided to do something different with this retrospective. Rather than spotlight an actor, I wanted to discuss an Asian artist working behind the camera. And I mean literally behind the camera.

In the collaborative enterprise that is filmmaking, few roles are as crucial as that of a cinematographer. After all, if no one was capturing the events with a camera, it wouldn’t really be a movie. But, of course, cinematography is so much more than simply recording action. It involves using light, shadow, focus and movement to enhance drama, and enrich the viewing experience. And few people knew that better than James Wong Howe, whose pioneering use of low-key lighting, wide-angle lenses, and the crab dolly won him two Oscars — for “The Rose Tattoo” (1955) and “Hud” (1963). His techniques were so groundbreaking and effective that they are still used and studied. I myself had to watch “Hud” while studying film at New York University, and I’ll admit, I was blown away by the striking, black-and-white imagery. I was even more impressed when I learned that the director of photography was Chinese American like me.

Born Wong Tung Jin in Taishan, James Wong Howe moved with his family to Washington State in 1904 when he was just five years old. After trying his hand at boxing from 1915 to 1916, he moved south to Los Angeles. There, coincidentally, he ran into an old boxing colleague who was able to get him a low-level job in the film lab at Famous Players-Lasky (now Paramount) Studios. It was while he was employed there that he came into contact with famed director Cecil B. DeMille, who also helmed Sessue Hayakawa’s breakout film, “The Cheat” (1915). Howe was called to the set of “The Little American” (1917) to act as an extra clapper boy, and DeMille liked his look so much that he kept him on and launched his career as a camera assistant. This, however, was not what led to Howe becoming a cinematographer. That actually came about by mistake.

To earn additional income, Howe took publicity stills for Hollywood stars. And while taking photos of Mary Miles Minter, he stumbled across a means of making her blue eyes look darker. Back then, photographers used orthochromatic film, which turned blue to white. So when Howe had her look at a dark surface, her eyes would actually appear in the photo, as opposed to simply showing up washed out. Minter was so impressed with his innovative techniques that she personally requested he be the director of photography on her next film, “Drums of Fate” (1923).

Despite his success, Howe’s life was anything but easy. Like many in his profession, he struggled when Hollywood abandoned Silent Films in favor of “talkies.” In fact, from 1928 to 1931, he barely worked, and it was only thanks to Howard Hawks, who hired him as the cinematographer for “The Criminal Code” (1931) that his career began to pick up again. And while he worked consistently during the 1930s and 1940s, he faced constant discrimination.

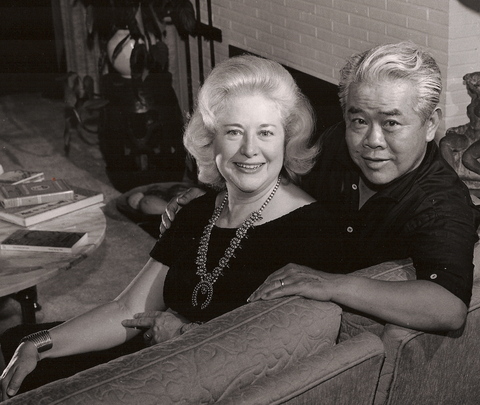

Due to the Chinese Exclusion Act, he was unable to obtain U.S. citizenship until the law’s repeal in 1943. Likewise, his marriage to the white novelist Sanora Babb, whom he married in Paris in 1937, was not recognized by the state of California until the law prohibiting interracial marriage was lifted in 1948. And even then, the couple couldn’t go public, since the “morals clause” in Howe’s studio contracts prohibited him from openly acknowledging his marriage. This fact was especially difficult for Howe. As his nephew, Don Lee, recalled in an interview, “[he] loved dogs, baseball, golf, and most of all Sanora.” The war years were also extremely difficult, with Howe actually needing to wear a “I am Chinese” button so as to avoid getting attacked for being Japanese. And that wasn’t even the worst of it. After the war, he was grey-listed, or deemed suspicious, by the House Un-American Activities Committee, due to his wife’s previous membership in the Communist party.

And yet, despite all of this — the racism, the xenophobia, the changing technologies and ever-shifting studio politics — Howe continued to be sought after and revered until his death in 1976. Directors like Martin Ritt and Daniel Mann loved working with him. Stars like Paul Newman held him in high esteem. He mentored an entire generation of A-List cinematographers, like Dean Cundey, who shot “Jurassic Park” (1993) and is on record stating that Howe’s lecture at UCLA was the most valuable class he took in film school. And unlike so many Asian American artists of his day, he was never pigeonholed into making certain kinds of movies due to his race. I still believe we should recognize and celebrate the talents of Asian American pioneers, like Sessue Hayakawa and Miyoshi Umeki. But if you’re looking for an Asian American trailblazer whose impact is still being felt throughout the industry, watch the films of James Wong Howe. He truly did change movies forever, and I, as both a Chinese American and a filmmaker, couldn’t be more grateful.