Written By: Nathan Liu

“The root of diaspora is pain; the pain of having to leave your homeland.”

This statement, made about halfway through the runtime, is the central thesis of “Jeronimo,” a documentary about Koreans in Cuba. A passion project of Korean American lawyer Joseph Juhn, the movie came about entirely through chance. While visiting Havana back in 2015, Juhn met a woman, Patricia, who just so happened to be a third generation Korean Cuban. She introduced him to the rest of the island’s small Korean community, as well as to the story of her father, Jeronimo Lim. This ultimately inspired Juhn to come back and make an entire film about the man.

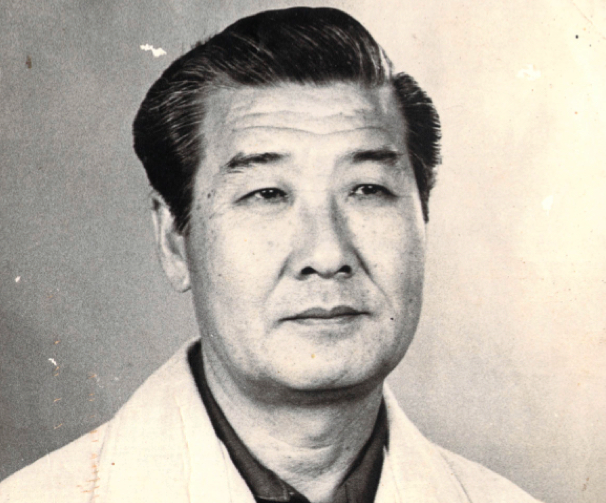

An ethnic Korean from the small city of Matanzas, Jeronimo Lim was classmates with Fidel Castro, fought in the revolution, and even worked in the intelligence service. Then, after rediscovering his Korean identity following an official visit to Seoul, he dedicated the rest of his time on earth to building a Korean community in Cuba. The details of his life and legacy are, technically, what the documentary is about. In reality, though, “Jeronimo” is a conduit through which Juhn can explore the Korean diaspora in Cuba, as well as diaspora in general. The picture actually opens with two definitions for the term, placing the concept front and center. The movie features interviews with several scholars, and even a rabbi, about the meaning of the word. And Juhn himself has made it clear that diaspora was the main element holding the project together while he was shooting.

“I didn’t know what I was going to make,” he explained at the documentary’s New York premiere. “And because I don’t come from a professional filmmaking background, I just kept on shooting for the next two years, and asking for funding and donations. I had a vague idea as to which direction I wanted to take this to, which is to talk about diaspora.”

He had no idea where the film would end up, and yet he knew he had to make it. His research, not just into Jeronimo Lim’s life, but into how all Koreans were treated in Cuba, convinced him that this was a story that needed to be taken out of the Caribbean. To use his own words, “… it needed to be shared with other Koreans.” So he returned to Cuba three times, endured the sweltering heat, and shot the footage, guerrilla-style, without any official permits. This last decision was born out of necessity. According to Juhn, “To get an official permit from the Cuban government, you either need a lot of money or connections. I had neither.” Nevertheless, he persisted because he wanted to talk about diaspora; a big, complicated, multifaceted subject, which varies based on location and time period. No single film, or work of art, could encompass the experiences of every single member of any one diaspora. And yet, to a certain extent, “Jeronimo” manages to do just that.

While this movie focuses on Koreans in Cuba and explores the specific conditions under which they arrived in the Caribbean, it manages to tap into larger themes that any person can relate to. That statement about the root of diaspora being pain is actually only half of what the person being interviewed in the movie says. The second, and more significant half of the statement is, “But the consequence, the result of that pain is innovation.”

This is a sentiment that I believe most immigrants and their descendants can relate to. Even if you arrive to a new country under the best of circumstances, you still lose something. You lose your birthplace. And even if you spend decades in your adopted homeland, you’re always caught in a strange limbo, not a native, but not from your birth country anymore either. That’s precisely what happened to my grandfather, a doctor from Guangzhou who spent two-thirds of his life in the United States, but always struggled to be fully seen as American. To put it simply, he spent the rest of his days trapped in uncertainty. And that uncertainty can be passed on to a person’s descendants as well. How often do we, as Asian Americans, question where do we belong? How often have people told us to “go back to your country” when the only country we know is the United States? And yet, this uncertainty, this pain born from losing our homelands, can force us to be creative.

According to the documentary, Jeronimo Lim spent the first half of his life wanting nothing more than to be Cuban. He didn’t attend Korean language classes, largely avoided Korean cultural events, and when the revolution happened and a new Communist government was established, he happily joined it. As Juhn himself so eloquently puts it, “Under Communism, certain ethnic groups, certain cultural groups, no longer have superior positions over others. Everyone’s a comrade.” He no longer had to be Korean. He could be fully Cuban.

And yet, after visiting Seoul, he found a new appreciation for his background, and a new understanding of the fact that he didn’t have to pick a side. He could be both Korean and Cuban. His efforts to create a Korean memorial in Manati highlight this fact. The monument celebrated the courage of those Koreans who came from afar, while recognizing their place in Cuban history. In short, Jeronimo felt pain. But that pain forced him to be innovative. I find this to be a thoroughly inspiring message, which, according to Juhn, is precisely the film’s intention.

“I wanted to empower whoever watches this,” he explained after the screening. “Jeronimo was 100% Cuban, and 100% Korean. Having that sense of dual identity is completely fine, and we should completely embrace who we are.”

That is a message that all people of all diasporas should experience. And that’s why I think everyone should watch this documentary. While it may be about a very specific group in a very specific country, the themes it explores — isolation from one’s surroundings, searching for identity — are ideas that I believe can speak to people everywhere. If nothing else, this film tells members of the Korean diaspora, as well as members of every diaspora, that they are not alone. And it’s good to be reminded of that every once in a while.

Director: Joseph Juhn

Stars: Jeronimo Lim

Running Time: 1 hour 40 minutes

Genre: Documentary